Early on in my research and prep for my retro-flection series on Suede, I read (and then re-read) Brett Anderson’s two autobiographies, Coal Black Mornings (from 2018) and Afternoons With the Blinds Drawn (2019). Music-related biographies are one of my favourite genres to read, but autobiographies are sometimes hit-and-miss affairs. I find them either dull due to a lack of imaginative writing or overtly boastful to the point of being unbelievable. Anderson’s memoirs were neither of these things. Poignantly verbose and lyrically poetic, these short tomes are essential reading for anyone remotely interested in understanding Suede’s creative arc and motivations. They are also a joy to read for the sheer thrill of Anderson’s handling of language, imagery, and humour, a skill that’s only hinted at by the very best of his lyrics.

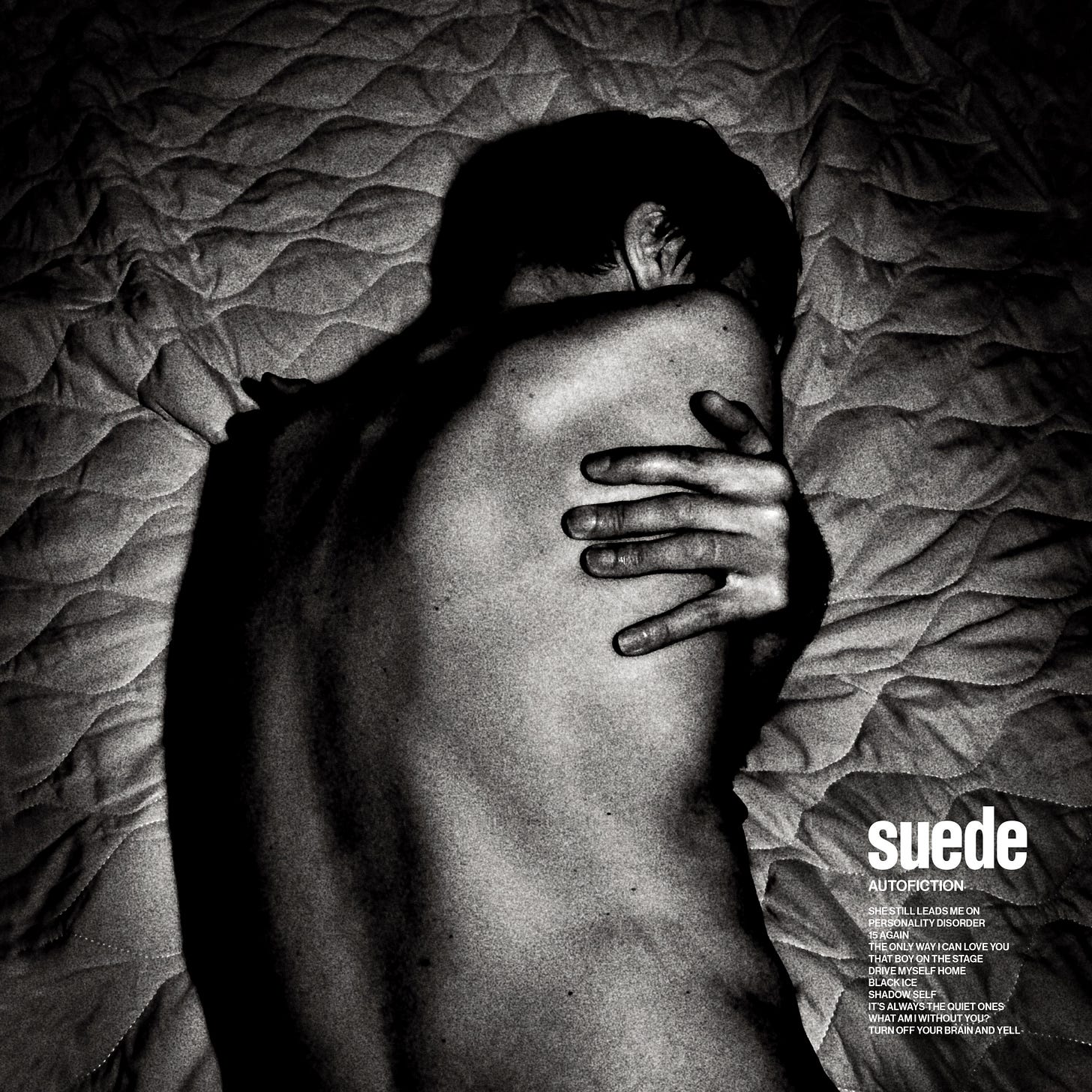

It's no surprise that Anderon’s memoirs landed between 2018’s The Blue Hour and Autofiction in 2022. Delving as deeply into his pre-Suede past as he does with Coal Black Mornings and the chaotic rush of fame covered by Afternoons with the Blinds Drawn, it feels inevitable that any subsequent Suede album would become an autobiographical exercise of its own. Like Anderson’s sharply observed and deeply personal musings, Autofiction looks back to a time of youthful naivete and conviction that moves Suede even further forward after Night Thoughts and The Blue Hour. Anderson called Autofiction Suede’s “punk” album, a reaction to their more sombre, cinematic post-reunion albums. There is no denying that Suede in 2022 sounded raw, urgent, and reactionary while also contemplative, influenced by Anderson’s introspection as much as the desire for a musical reset. That balance lies at the heart of Autofiction, the next chapter in Suede’s evolution, reframing history and memory through the sharpened lens of age, experience, and renewed vitality.

Punk is such a loaded word. It has always been associated with youth in revolt, a rejection of societal norms and middle-aged complacency or anything that smells remotely like the establishment. In its mid-70s heyday, I don’t think any punk would have ever conceived of the possibility that a 50-year-old could be punk, let alone imagine themselves at that age. And yet here we are: John Lydon, punk poster-child, will turn 70 in 2026, and is still as anarchistic as ever. I’m over 50 myself, and guilty of smirking at the notion of ‘middle-aged punks.’ Still, I have to concede that, as someone who doesn’t identify with the soccer moms-and-dad set in the least, ‘punk’ has come to mean less a stage of age and more a state of mind.

So it feels somewhat subversive and oddly fitting that Suede would open their so-called punk album with a spiky, angular guitar anthem that wrestles with very adult themes: the consternation and contemplation that comes with the death of one’s parent. “She Still Leads Me On” bristles with Richard Oakes’ acerbic and wiry guitars, but beneath its punk posturing, Anderson wrestles with the very real experience of mourning his mother’s death while still fully engaged in a relationship with her through his memories. As he sings (after a barely audible spoken-word intro), “When I think of all the things my mother said / When I think of all the feelings I hid from her / Oh in many, many ways, I’m still a young boy,” a lump catches in my throat and tears well up in my eyes. Anderson’s mother died when he was in his early 20s; my father died when I was 26. Change the parent and pronouns, and he might as well be singing about my own experience.

At 6:00 am on August 7, 2025, I had officially lived longer without my father than with him. That shit is real. When those kinds of realizations hit, they hit hard, and they strike deep, and they leave you raw, wounded, and highly vulnerable. So when Anderson cries out, “Sometimes, oh when I just feel like screaming / She leads me on, she still leads me on,” I know exactly what he’s feeling, and the holy racket he and the rest of Suede are playing makes perfect sense to me. That’s pretty punk, no?

As its title suggests, Autofiction isn’t strictly a memoir set to melodies; it marries Suede’s flair for world-building with lived experience to shape 11 sharp vignettes of modern middle age, each one shot through with punk’s restless energy. Not all of them land with the same emotional weight as “She Leads Me On,” but there’s no sense that Suede are resting on their laurels nine albums and thirty years into their career.

I love the spoken verses on “Personality Disorder,” as they feel so perfectly appropriate for the stark truths Anderson intones: “And our lives too will fall apart like this moment / Gone like the birthday cards on the windowsill / Brief as the pale light on the bedroom walls.” His lyrical imagery is as vivid as the prose in his books, and the band invests the song with spunk and teeth. The energy on “Personality Disorder” makes up for the somewhat formulaic and predictable “15 Again.” Anderson’s phrasing, in particular on the chorus, feels awkward, forced, and out of sync with an otherwise decent band performance.

Similarly, “The Only Way I Can Love You” is one of those songs that I feel neutral about. I get the sense that it's become a fan favourite, and it works in the context of Autofiction’s other songs, but it doesn't stay with me once it's over. “That Boy on the Stage” fares better as an earworm. Its highly meta lyrics and strident guitar riffing remind me a lot of Manic Street Preachers, with whom Suede co-headlined a North American tour in 2022, one I almost went to before COVID concerns got the better of me.

It’s not until Autofiction’s halfway point that my heartstrings really get tugged again like they did with “She Leads Me On.” The elegaic and elegant “Drive Myself Home” is Suede canon from its very first chords. It’s pure and simple, what Suede do best. Its subtle, sustained piano motif, chiming guitars, and Anderson’s tender, mournful delivery feel like a response to one of their early B-sides, but this time without needing to prove anything.

There have been frequent cold and winter references that come up in Suede’s discography since Bloodsports, and “Black Ice” is the most aggressive and pointed of the lot. For Anderson’s family’s sake, I hope “Black Ice” is more fiction than autobiography. “Well you made me a father / And I gave you my name,” he slurs on the opening verse before launching into the careening chorus: “We’re on the black ice with no headlights / With our hands off the wheel.”

Drummer Simon Gilbert and bassist Mat Osman keep the momentum moving with the taut rhythms on “Shadow Self,” where Anderson deploys more spoken word delivery on the verses. Of all the moments on Autofiction, “Shadow Self” feels most informed by a new generation of artists; I hear echoes of Fontaines D.C. in its ruggedness. “It’s Always the Quiet Ones” goes back to an earlier influence, channelling the ghost of Joy Division’s icy detachment through Neil Codling’s gossamer synths.

“What Am I Without You?” makes the hairs stand up on the back of my neck. Gilbert’s soft cymbals give me chills, and Anderson sounds so intense and passionate on what’s arguably one of his best vocal performances. The verses are tender and muted, so when the chorus comes in all big and bold, the song instantaneously becomes a stadium-ready, lighters-aloft moment, their own “Fix You” (though I’m sure they’d hate me for suggesting the connection). I have not looked deeply into the album’s overall reception or how the fanbase feels about “What Am I Without You?,” but for me, this is canon, destined for any best-of-Suede playlist I make.

Suede ends their punk album with a song that is in no hurry to get to its payoff, and it’s all the better for it. “Turn Off Your Brain and Yell” has an elongated intro that, for some reason I can’t put my finger on, reminds me of the Cure. I found a poll on a Facebook Suede fan forum ranking their closing songs, and while it’s no “Still Life” or “The Next Life,” “Turn Off Your Brain and Yell” betters “Saturday Night” and is miles ahead of all the others. The shower of static and abrupt unplugging sounds at its end feels like a portentous note — a swan song if Autofiction had been their final statement, or a possible signal of the path they’re taking with the forthcoming album, Antidepressants.

Refusing to abide by expectations is not the sole domain of the twentysomething crowd, and Autofiction proves that old geezers can be punk into their pensioners’ era. Suede still sound raw and vital in their fifties, transforming the personal into universal experiences and building worlds that feel intimate and immediate. Anderson may have begun with his memoirs, but Autofiction feels more forward-thinking and progressive than reflective and nostalgic. I started this retro-flection series thinking Autofiction would be the last word, but the announcement of Antidepressants mid-way was proof that even in middle age, Suede are still capable of a bit of chaos. That’s pretty punk, no?

![the act of just being [t]here](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!moQy!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fedc03f78-2893-4045-9600-2bacb96b8fa5_1080x1080.png)

![the act of just being [t]here](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!pLeR!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0d02a71c-d57a-4a4b-b90c-22191b1e1244_2688x512.png)