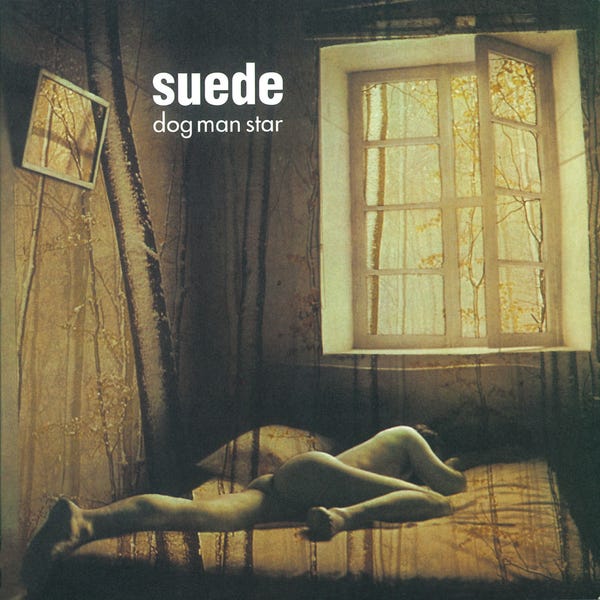

Some thirty years after its release, the gall of Dog Man Star impresses me most. Yes, yes, the music is spectacular—leaps and bounds ahead of its predecessor and a high watermark they have yet to eclipse. Yet, when you place Suede’s sophomore album in both the context of 1994’s musical landscape and the severing alliances within the band, Dog Man Star casts a long and legendary shadow that is hard to shake.

Before going any further starting, I heartily accept that anything I write about this period for Suede will feel woefully inadequate compared to Matthew Lindsay’s thoroughly engaging 2014 essay on the silver anniversary of Dog Man Star for The Quietus. For my part, I’m focusing in on two critical contexts for understanding why Dog Man Star is such a singular album: the internal state of affairs between the members of Suede at the time of recording it and the external state of the music scene in Britain at the time, widely—and pejoratively—referred to as Britpop.

7 March 1994: the UK is still in winter’s grip, cloudy, cold, and covered in drizzle, when Blur drops what will become the song of the spring, summer, and fall. “Girls & Boys” is the first single from their forthcoming third album, Parklife. For some, it perfectly articulates the patriotic attitude Select magazine reported on a year earlier when they pasted Suede’s Brett Anderson in front of the Union Jack on their April 1993 cover under the headline “Yanks go home! Suede, St. Etienne, Denim, Pulp, the Auteurs, and the Battle for Britain.” That issue of Select is widely credited with giving birth to Britpop, following a gestation period that arguably began with Suede's debut, “The Drowners.”

Anyone who read my earlier post about my voracious appetite for new music and my need to be ahead of the cultural curve will not be surprised that the April 1993 Select was a formative text in my musical taste development and a shopping list. That issue is why I went out and bought import copies of Denim’s Back in Denim, the Auteurs’ New Wave, and Pulp’s His N Hers (it would take a year and Tiger Bay before I got into St. Etienne, and, though Select did not include Blur in their article, another key album from 1993 for me was Modern Life is Rubbish). If Select wrote anything remotely positive about a band or album, you could bet I’d do whatever it took to hear it and own it. I will spare you a “Was Britpop a real thing?” debate; like most musical movements, it wasn’t a thing until someone started calling it a thing, and then it became something other than an actual movement. As the UK music press latched onto the idea of Britpop and began articulating what it meant in print, most musicians associated with it rejected the label, none more vociferously and adamantly than Suede.

Before Blur and Oasis (who debuted with “Supersonic” a month after “Girls & Boys”) would dominate the spring and summer of 1994, Suede released the non-album single “Stay Together” in February. It would be their last release while guitarist and songwriter Bernard Butler was officially a band member. While Brett Anderson dismisses “Stay Together” as “very much below par for [Suede] and lyrically … anodyne to the point of meaninglessness,” it is far from a stop-gap single. “Stay Together” sits squarely in the centre section of the Venn diagram where Suede’s internal dynamics overlap with the external musical ethos they were pushing against.

“Stay Together” is an eight-and-a-half-minute tug-of-war between Suede’s chief songwriters. It begins as a pop song that evolves into a complex, extended psych-rock jam. It was Butler’s most ambitious and dynamic composition and, self-admittedly, one of Anderson’s least inspired songs lyrically (“A collection of tired Suede-by-numbers urban landscape clichés and second-hand emotional posturing,” as he described it in his 2019 autobiography, Afternoons With the Binds Drawn). “Stay Together” essentially finds all of Suede with one foot in their former life as the do-no-wrong, next-biggest-band-in-Britain and the other planted in the murky abyss created by the expectations and pressures of following up the success of their debut.

As with most battles of wills, there is no winner. “Stay Together” gave Suede their highest placement in the singles charts up to that point, but even with a radio-edit version, its ambitious reach never caught the same euphoric highs of their early singles. It would eventually be overshadowed by its B-sides “The Living Dead” and “My Dark Star,” widely considered by fans as two of the best songs in the band’s canon. Still, its chart success gave Suede the go-ahead for what both Butler and Anderson had in mind for Suede’s next album. With “Stay Together” as a blueprint, Dog Man Star became a monolithic manifesto, a brilliantly sore thumb sticking up amid Britpop’s increasingly cartoon-like schtick that would forever be remembered for the end of Anderson and Butler’s songwriting collaboration as members of Suede.

The tell-tale signs of an imminent demise were evident well before the band stepped into the studio to record Dog Man Star. While chasing the dragon of American success on their 1993 North American tour, Butler felt at odds with his bandmates’ indulgent and decadent behaviours. He reportedly spent his off-stage time alone or with the crew and opening act, the Cranberries, rather than with Anderson, drummer Simon Gilbert, and bassist Mat Osman. When his father died that fall, Butler found himself in an emotional tailspin that pitted his band and family responsibilities against one another. As Anderson, Gilbert, and Osman admit in the 2018 documentary Suede: The Insatiable Ones, it was a mistake to forge ahead with tour plans and not allow Butler the time and space to grieve. Instead, he channelled his sorrow and loss into “Stay Together” and the demos and sketches destined for Dog Man Star.

The chasm opening between Butler and his bandmates was emotional, philosophical, and physical. Dog Man Star was primarily composed by mail; Butler would send cassettes of instrumental demos to Anderson, who in turn would work up lyrics and send the tape back via return post. An interview Butler gave to Vox magazine, in which he appeared to criticize Anderson openly, exacerbated the acrimony and growing fissure between the two collaborators. Not surprisingly, studio sessions usually had the two on separate schedules, with Butler working alongside—and by many accounts, over the top of—producer Ed Buller, and driving further wedges between himself and Gilbert and Osman with his hyper-focused, dictatorial attention to their playing. It’s clear with hindsight that Butler’s frustrations with Buller’s production and his exerting control over the musical direction and production style of the record were a means of satisfying a need for stability and control in his personal and professional life. Yet, by summer’s end, with the bulk of production work done, Butler and Suede officially parted ways. Buller and the rest of the band completed the final touches on Dog Man Star without him.

You would think that a record created under such circumstances, where the principal songwriters need stamps to communicate with one another and cannot see eye to eye on what the producer is doing, would be an unmitigated mess, a disjointed disaster, and a critical failure. It’s what the press was smelling when they first caught wind of the split: a spectacular fall from the impossibly high pillar they put Suede upon some twenty-four months prior. And though it had its detractors (Butler chief among them), Dog Man Star achieved what many believed impossible at this point in Suede’s story: a sophomore album of cinematic scope and breadth that eclipses its predecessor.

Dog Man Star amplified every extravagant dystopian idea Anderson had in reaction to Britpop while showcasing Butler’s expansive experiments in atmosphere and textures. As acrimonious as it was, Butler and Anderson’s frayed relationship pushed them higher and further with each song. They may have been at odds personally, but artistically, they were two hearts under nuclear skies reaching for a transcendent state of artistic achievement that few of their contemporaries dared to consider. More Joy Division, less Smiths. Less Gary Glitter, more Scott Walker. Infatuated with old Hollywood chic, contemptuous of cool Britannia. Dog Man Star put everything on the line with audacious confidence and bold, brash imagery and style. Where Suede felt more like a collection of songs, Dog Man Star was a complete package.

Their musical evolution is evident from the outset, as witnessed in the opening track, “Introducing the Band.” Butler’s dirge-like, repetitive droning music sounds nothing like the chiming guitar riffs of the debut album, and Anderson meets the moment with a Buddhist-chant-inspired mantra culled from dystopian fiction and rooted in self-mythologizing bravado. Dog Man Star gets its name from the opening line of “Introducing the Band:” “Dog Man Star took a suck on a pill / And stabbed a cerebellum with a curious quill.” The title is the first of the album’s cinema references, cribbed from Dog Star Man, a series of short experimental films directed by Stan Brakhage, that presented in its entirety, is a single work in four acts and a prelude. Intentionally or not, there is a similar structure to the sequence of Dog Man Star, with its first two songs in the role of prelude. Whether you hear it as a warning or a war cry, “Introducing the Band”’s implicit tone sets the stage for the world burning that’s to come.

Suede wastes no time in setting the fire with Dog Man Star’s first single and second track, “We Are the Pigs.” A riotous call to arms, “We Are the Pigs” positions Suede as the anti-establishment, working-class saviours come to rescue us all from the middle-class posers. Released as a single in September 1994, “We Are the Pigs” could not be any more opposed to what was happening in the UK music scene at the time. While Oasis were feeling supersonic and flush with the first washes of fame and Blur were following the herd on holiday in Greece, Suede were setting police cars on fire, waking up with guns in their mouths and declaring themselves swine and “stars of the firing line.”

As Dog Man Star moves from its Orwellian prelude to its film-themed first act, its music and subject matter (at least superficially) become more cinematic. The action moves from riots on the streets to tumbles in the sheets, so to speak, where “Heroine” finds Anderson’s Byron-quoting narrator in the throes of “pornographic and tragic” obsessions. The lyrical layers and competing subtexts in “Heroine” come fast and furiously and can leave you as mentally spent as its rub-and-tugging teenage protagonist. Aside from the ambiguity and interchangibility of ‘heroine’ and ‘herion,’ Anderson is purposefully opaque as to exactly which Marilyn (Monroe or porn actress Marilyn Chambers?) he’s referring to in the lyrics. What is clear is that “Heroine” signals a level-up in Anderson’s songwriting away from the simpler verses and catchy hooks of the debut album and into more developed character studies and innuendo.

“Daddy’s Speeding” is more straightforward lyrically, training its spotlight on actor James Dean, the patron saint of dissaffected and alienated youth the world over. It stands out as one of Butler’s most unexpected compositional turns, straying away from Suede’s guitar-driven pop formula, employing texture, ambience, and production overlays to deliver a careening and explosive interpretation of the car crash that claimed Dean’s life.

If the unconventional composition of “Daddy’s Speeding” was Butler taunting Anderson to come up with suitable lyrics, then “The Wild Ones” (borrowing its name from the 1953 Marlon Brando film) is the synergistic apex of the duo’s songwriting collaboration, and, as writer Miranda Sawyer suggests in her book Uncommon People: Britpop and Beyond in 20 Songs, Suede’s best single ever. A gorgeous ballad of timeless beauty that portends the end of Butler’s stint in the band (“And there's a lifeline slipping as the record plays / As I open the blinds in my mind, I'm believing that you could stay”), “The Wild Ones” serves double duty as Dog Man Star’s second single and spiritual heart. Amidst all the dystopian chaos and careening car crashes surrounding it, “The Wild Ones” is an affecting and deeply moving portrait of the tug-of-war between human relationships.

Like a muddy puddle that’s best stepped over than into, Dog Man Star’s next act is its most skippable. “The Power” is a cookie-cutter piano-led self-congratulatory slap on the back, celebrating Anderson’s successful climb out of his working-class heritage, finished in the studio after Butler left. “New Generation” is equally anodyne and disposable (and oddly, the album’s third and final single). In Afternoons With The Blinds Drawn, Anderson suggests it is about his former romantic partner and ex-Suede member Justine Frischmann’s success with Elastica: “It was meant as a song of love and encouragement for her, the bitterness forgotten, the scar tissue healed.” Passable as pop songs as they are, in the overall context of Dog Man Star, “The Power” and “New Generation” leave a mark on the album that dulls its shine.

It’s not until Dog Man Star’s second, most thrilling and challenging half that the stark contrast between where Suede was in 1993 and the prevailing musical climate around them is thrown into bold and beautiful relief. For anyone listening to Dog Man Star on cassette or vinyl in 1993, flipping it from Side A to B was like entering the Upside Down on Stranger Things: oddly familiar and frighteningly foreign. The distorted horn blast at the top of “This Hollywood Life” serves as a warning that what’s coming is darker, seedier, and seductively more alluring than hip-swaying, hand-clapping fans of “Metal Mickey” might be bargaining for. Built upon a solid blues rock riff and featuring one of Osman and Gilbert’s best turns as a rhythm section, “This Hollywood Life” kicks off the album’s third “careful what you wish for” act with a rags-to-riches-to-fall-from-grace story of a “she-rocker” riding the wave of fame, a parable of the band’s trajectory. Somehow, the band made it sound raunchier and snottier when I saw them play it live as the opener at Toronto’s Warehouse on February 17, 1995, Anderson wielding his walking cane (due to a fall earlier in the year) like a carnival barker enticing his prey into his big top of terrors and delights.

“The 2 of Us” turns down the volume and energy but never lets up on the emotional throttle. For many, “The 2 of Us” has become a poignant allegory to Anderson and Butler's story, centred around a pair of high-rolling financiers who find themselves flush with cash and devoid of fulfillment. In Afternoons With The Blinds Drawn, Anderson recalls watching the song come together in the studio and being in awe of Butler’s gifts and grasping the alchemy the two had as songriters: “The parallel with my and Bernard’s position, even though not at the time consciously intended, has over the years revealed itself to me as possibly its true meaning, but like I have said before, songs will often slowly and mysteriously uncover themselves, even sometimes to the writers.” In an unexpected and odd bit of sequencing, the subpar and somewhat disposable ballad “Black or Blue” follows “The 2 of Us” to its detriment. Where “The 2 of Us” is Anderson and Butler’s collaboration in full bloom, “Black or Blue” withers as they turned their backs on one another, with Butler’s contributions recorded after his official split as a final contractual obligation.

Where Dog Man Star’s final act starts is immaterial; whether it’s before, after, or mid-way through the penultimate track, “The Asphalt World,” the album’s two-song coda is the crowning glory on both Dog Man Star and Butler’s time as a member of Suede. In 2013, Stereogum omitted “The Asphalt World” from its list of the 10 best Suede songs, a correction the Guardian fixed in 2014. Both omission and inclusion are likely due to the same reason: the song’s un-Suede-like nature. Butler envisioned an epic and audacious 20-minute guitar-driven elegy that would fill an entire album side; producer Buller and the other members pushed for the nine-minute version that made the album. According to many accounts, the track became the catalyst for Butler’s departure. In later years, Anderson would reveal that he recorded the song’s sordid lyrics about a lover’s flagrant betrayal on the same day he read the aforementioned interview Butler gave Vox, pouring his emotions into his best performance on the album. It took time (20 years, almost) and perspective for me to fall in love with “The Asphalt World,” a song that is now such an essential part of Dog Man Star for me that I need to stop what I’m doing whenever it comes on and fully give myself over to it.

Neither Stereogum nor the Guardian include “Still Life” on their list of best Suede songs, which doesn’t surprise me, given the closing track’s affected and over-the-top orchestration. Over the years, I have vacillated between feeling like “Still Life” is “too much” and “not enough.” Currently, I’m of the mind that it could have benefited from some editing in the song’s final moments, but it is still exquisite even in its imperfection. Anderson revisits the maudlin lives of unfulfilled housewives he first introduced listeners to on the debut album’s “Sleeping Pills,” and enfuses their kitchen-sink drama about looking outward at a what-could-have-been existence with vocal acrobatics heretofore untested on record. The orchestra swells as he pushes the limits of his range, and so too does the song and the album’s emotional rush. Where “Introducing the Band” kicks off Dog Man Star with a foreboding and menacing attack, “Still Life” floods the senses with serotonin that never ceases to bring tears to my eyes. It’s ridiculous to think that what’s essentially a pop song like this can choke me up every time I hear it, which is a testament to Butler’s musical acumen; he doesn’t get nearly enough credit for how attuned he was to music’s power to move the listener’s emotions, which is essentially the secret sauce that makes his work with Suede so special.

Some albums end with a suggestion of where the artists are heading next, while others put a bow on a chapter and leave a clean slate moving forward. Even if Butler had somehow managed to remain in Suede and the band members repaired their relationship enough to move forward, Dog Man Star would be one of those latter albums. In a musical landscape where their contemporaries were more focused on competing in the singles charts, Suede set about creating a proper record —a fully realized concept album that went so far against the prevailing trends that it remains timeless and peerless.

Dog Man Star is the ideal denouement to the Bernard Butler chapter of Suede, and a thoroughly satisfying conclusion to the musical partnership that set their trajectory in motion. It put everything on the table, and though it left the relationships between Suede fractured, there is no unfinished business left to explore; it is imperfect, but it is enough.

![the act of just being [t]here](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!moQy!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fedc03f78-2893-4045-9600-2bacb96b8fa5_1080x1080.png)

![the act of just being [t]here](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!pLeR!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0d02a71c-d57a-4a4b-b90c-22191b1e1244_2688x512.png)