“Listen”

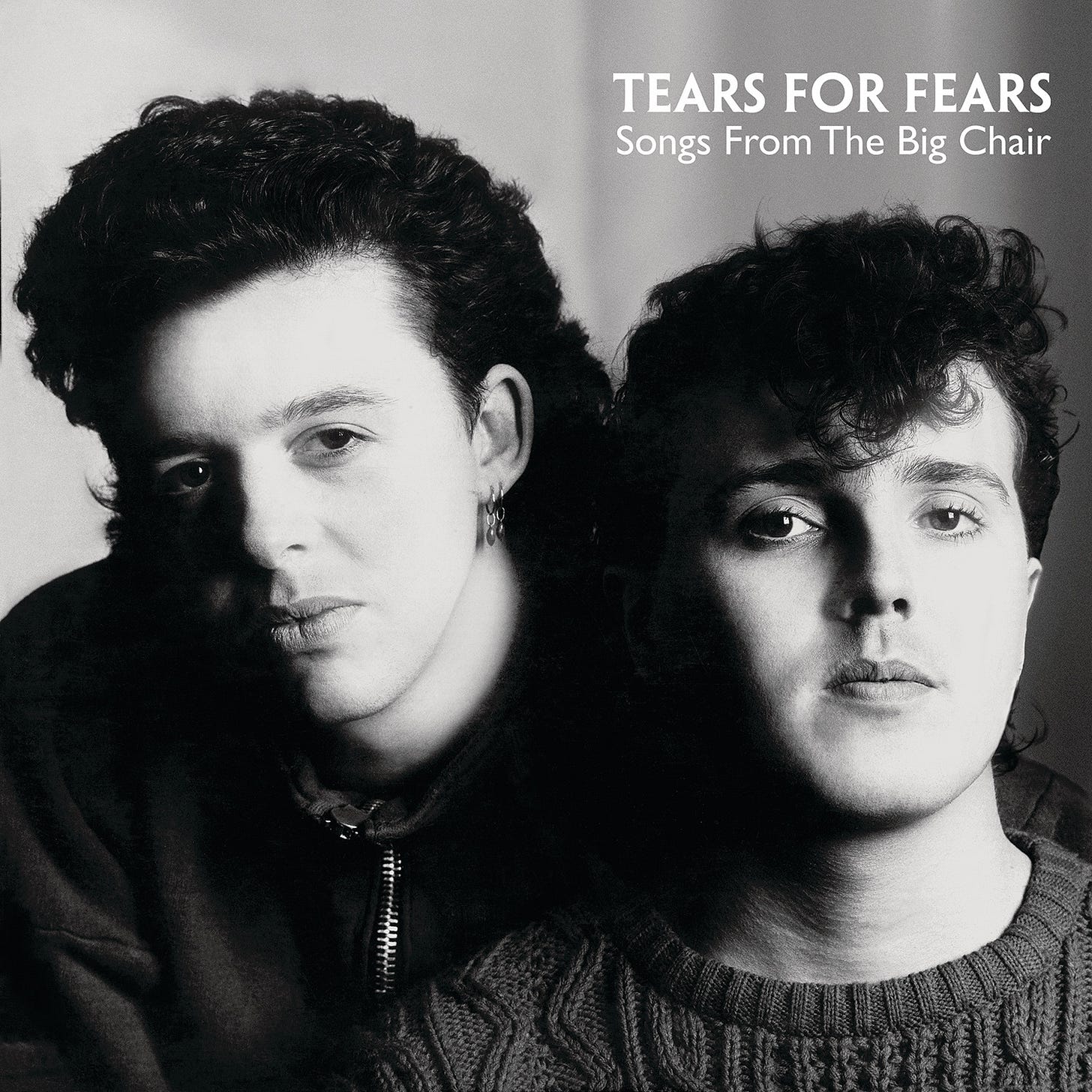

Funny how the 1980s anxiety and angst of Tears For Fears’ Songs from the Big Chair feel uncomfortably familiar for a forty-year-old album.

Remember COVID? More precisely, remember that feeling around May 2020 when we lost track of how long we had been in lockdown and completely forgot what pre-pandemic life was like? We couldn’t even pretend to have a real life on social media, because social media had become our real life and the only place most people could connect.

What does any of this have to do with Tears For Fears and Songs from the Big Chair? It was during this precise time in lockdown that an old university acquaintance shared the “10 Influential Albums in 10 Days” Facebook meme, in which he featured Tears For Fears’ 1983 debut album, The Hurting, with the comment, “Better than Songs from the Big Chair.” Taking the bait, I commented back, “Them’s fightin’ words, mister,” prompting him to reply: “They were meant to be.”

I’ll spare you the details about how this exchange set me off on a pandemic-sized quest to research and read every think piece I could about Songs from the Big Chair, and how I started formulating my pitch to write 331/3 for a book on it (at the time I was shocked there wasn’t already one in the series, and still can’t believe there isn’t one now). Suffice to say, when I make out lists of albums I wanted to write about on this Substack, Songs from the Big Chair is always close to the very top. I would argue it’s one of the defining albums of the 1980s, quintessentially of its time and a record that remains as relevant in 2025 as it was in 1985.

If there is one thing you need to know about Tears For Fears, amongst all the relevant details of their formation and influences, it is that the core duo of Curt Smith and Roland Orzabal formed in 1981, and were heavily influenced by the work of American psychologist Arthur Janov, who pioneered primal therapy and famously counted John Lennon among his patients. They adopted the name Tears For Fears from a central tenet of Janov’s work: that our repressed childhood trauma—our tears—informs the neuroses, phobias, and fears we develop as adults.

Orzabal turned his deep interest in Janov’s work into an exploration of his own childhood traumas on The Hurting, the band’s 1983 debut album. Song titles were lifted directly from chapters of Janov’s books (“Ideas as Opiates”), and his ideas bled into the music’s icy synth sheen through Orzabal’s lyrics on songs like “Mad World,” “Change,” and “Suffer the Children.” Not exactly the stuff of top 10 hits and Top of the Pops appearances, and yet Tears For Fears managed both. In 1982, “Mad World” peaked at #3 on the UK charts and “Change” at #4, and a re-recording of “Pale Shelter” (originally released as a single in 1982 that never charted) made it to #5 in 1983.

While Janov’s influence is writ large all over the concept of the Hurting, it wouldn’t be until Songs from the Big Chair that Tears For Fears managed to bring his message to the masses through that record’s juggernaut opening track. As the story goes, Orzabal programmed a relentless and repetitive rhythm into a drum machine, paired it with a simple synth line and spare percussive flourishes, and then repeated the song’s improvised central theme, inspired by Janov’s primal scream therapy.

A song more about political protest (according to Orzabal) than personal therapy, it is hard not to read either topic into “Shout,”✦ with its rally-cry-like chorus and pointed verses about railing against “the things [we] can do without.” “Shout” was a stone-cold hit on delivery. It is wracked by Cold War anxiety that feels almost more relevant today as fascism, racism, and a blatant disregard for the dignity of humankind spread like a supervirus in our own backyards as opposed to countries on other continents.

Over its six-and-a-half-minute runtime, “Shout” swells to a cathartic anti-climax that never fully resolves its tension. Instead, it segues into one of the album’s signature ballads, “The Working Hour,” a call-out to the music industry’s exploitation of artists that predates the current era of streaming injustices by decades. Though it glistens with the highly polished production values of its time, “The Working Hour” could just as easily be about today’s music industry landscape, as musicians face shrinking royalties, cancelled tours, and a marketplace where even celebrated releases struggle to provide artists a sustainable livelihood. 1980s excess and 2020s precarity are more closely aligned than they might appear.

In 1985, 11-year-old me hated “The Working Hour.” I also frequently skipped over “I Believe,” “Broken,” and “Listen,” a full half of the album’s eight tracks. Although I didn’t have the words or musical knowledge to describe it as such, I didn’t enjoy or appreciate the jazzy and proggy experimentation facet of Songs from the Big Chair until much later in my adulthood, when I would listen to the record as a continuous whole on CD versus vinyl that required flipping halfway through. In hindsight, my reaction wasn’t unusual: many listeners gravitated toward the big singles and dismissed the rest. Now, though, I value the balance they provide and the bridges they create that bind the complete album together—an element that I feel Tears For Fears’ debut album lacks.

“I Believe” slows the pace with a jazz-inflected ballad that spotlights Orzabal’s vocals in a way the bigger singles rarely do. “Broken” serves as both connective tissue (reappearing for a slight return immediately after “Head Over Heels”) and a reminder that in 1985, we weren’t entirely out of arty prog-rock’s grasp yet. Closing track “Listen” layers the band’s signature synth textures with new-age chants for a meditative finale that leaves you in a state of suspended animation. That said, its reliance on “world music” tropes feels like an artifact of mid-80s production trends that today comes uncomfortably close to cultural appropriation. Still, I always think of its last notes as a deep inhale, as if the album is holding its breath for whatever happens next.

Songs from the Big Chair is still very much of its mid-1980s time, and I’m sure that for many who came to it for the big singles, Side B’s more esoteric moments can feel a bit stylistically schizophrenic compared to its stacked Side A. Not surprisingly, the album’s title is taken from another relic of its time, the 1976 two-part TV movie Sybil, starring Sally Field as a woman living with dissociative identity disorder. Field’s character finds solace in her therapist’s big chair, and in much the same way, the band retreated into these eclectic recordings as a way to find peace from the critical lashing The Hurting received from Britain’s fickle music press.

One song that didn’t initially bring Orzabal any peace or joy ended up as Tears For Fears’ biggest hit ever. “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” was the last track completed for Songs from the Big Chair, and at first blush, its bubbly beat and light touch feel miles from the angular edges of “Shout.” Once the song’s extended intro settles into the first verse, and Smith begins singing, its bright surface is darkened by its lyrical unease: “Welcome to your life / There’s no turning back / Even while we sleep / We will find you.” The underpinning menace and threat of power, corruption, and the lies being sold to the general public to cover up both make “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” one of the most unlikely of Top 40 hits, but it conveyed the deep-seated anxiety and skepticism brewing at the time. With 1984 only just behind us, the cultural shadow of Orwell’s Big Brother was unavoidable. The book’s vision of state surveillance and truth being twisted to fit official narratives felt less like science fiction and more like a mirror of the era’s military, nuclear, and geopolitical tensions. Tears For Fears tapped into that climate of mistrust and uncertainty, packaging it in a song that somehow still became a massive mainstream hit.

As if to counter the skiffle beat and pearly piano riffs on “Everybody Wants to Rule the World,” Tears For Fears follow it with “Mother’s Talk,”✦ the album’s dense and claustrophobic first single (released in August of 1984). Choppy rhythms and heavy synths compound the nervous energy of Orzabal’s fractured vocals. Lyrically, “Mother’s Talk” is the most paranoid moment on Song From the Big Chair, with anxiety-inducing imagery of nuclear-age fears, impending climate disaster, and a planet teetering on the brink of a global meltdown.

That intensity clears on “Head Over Heels,”✦ the album’s most unabashedly romantic track and arguably its poppiest moment. Built on a chiming piano riff and lush harmonies, “Head Over Heels” softens the sharper edges on Songs from the Big Chair. Still, Orzabal can’t help but undercut the sweetness with a sense of desperation, admitting that intimacy is fragile and fleeting in a world spinning out of control. Both tender and uneasy, “Head Over Heels” is as close to sentimental as Tears For Fears get, providing a late-album breather between the album’s moments of paranoia and confrontation.

Songs from the Big Chair is indelibly tied to the 1980s, thanks to its standout singles, but it is rarely appreciated as a collective work that stands on its own merits. It is frequently ranked in the lower echelons of best albums from the 1980s: an 87 from Pitchfork in 2018, and a more respectable yet criminally low 47 from Paste in 2020, where Josh Jackson rightfully acknowledges that many artists and producers at the time “toyed with the same tricks, giving songs a shorter shelf life.” But we are now in a time where age is immaterial, and music consumers are drawing from every era to curate their own personal playlists. Many of Songs from the Big Chair’s tracks, like “Shout” and “Mother’s Talk,” are poised to soundtrack our maddingly fast-paced, changing modern world, ready for their TikTok moment. What sets Tears For Fears’ sophomore album apart, though, is that beyond the hits and viral potential, it still speaks to the same anxieties about power, manipulation, and human connection that it did in 1985. Those themes have only grown sharper forty years on from its initial release, making Songs from the Big Chair feel less like a period piece and more like a warning we still must heed.

Funny how time flies, but the more things change, the more they stay the same.

![the act of just being [t]here](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!moQy!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fedc03f78-2893-4045-9600-2bacb96b8fa5_1080x1080.png)

![the act of just being [t]here](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!pLeR!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0d02a71c-d57a-4a4b-b90c-22191b1e1244_2688x512.png)

When the deluxe/expanded SftBC came out, I assembled a playlist of just the original album tracks and studio b-sides (so: no live/extended), then played it on random. A much richer listening experience; it feels almost analogous to OMD's "difficult" (but brilliant!) DAZZLE SHIPS — in fact, I do wonder if the latter vaguely influenced the former, or at least acted as a spiritual bridge to what it became.

Also some years back, I recorded a sax-heavy, but otherwise fairly faithful, cover of "I Believe." You're under nae obligation to (ahem) listen. ;)

https://garygahan.bandcamp.com/track/i-believe