The parallels are striking—almost blatant. A singer and guitarist, the former serving as the lyricist and the latter as composer, create what appears to be a preternatural, symbiotic songwriting partnership. Their sound builds upon the musical pillars of their youth, an amalgam of glammy rock, shimmery pop, and a dollop of punk’s DIY ethos. Lyrically, their songs skew more brooding than their contemporaries; a moody mix of winsome wit and carnal desire wrapped in narratives and examinations of modern working-class struggles, peppered with references to sex and pharmaceuticals. Their workhorse dedication to songwriting fuels the growing buzz around the band, and when the press takes a shine to them, the fanaticism builds quickly. A deal gets inked, and the accolades pour in with each successive single. The music papers declare them saviours from the schlock and pap of the pop charts, harbringers of a new aesthetic.

There was a sense of deja vu in 1992 when Suede emerged as “the best new band in Britain,” the press anointing them the second coming of the Smiths despite not having released any music at that point. By the start of the 90s, the first wave of shoegaze had already come and gone, the Stone Roses were still MIA, and Nirvana and their ilk had (momentarily) overtaken the broader musical discourse. The UK music press was ripe for a new homegrown obsession, and Suede perfectly filled that void, dressed for success in too-tight crimpolene blouses and worn Wallabees right out of the high street charity shops.

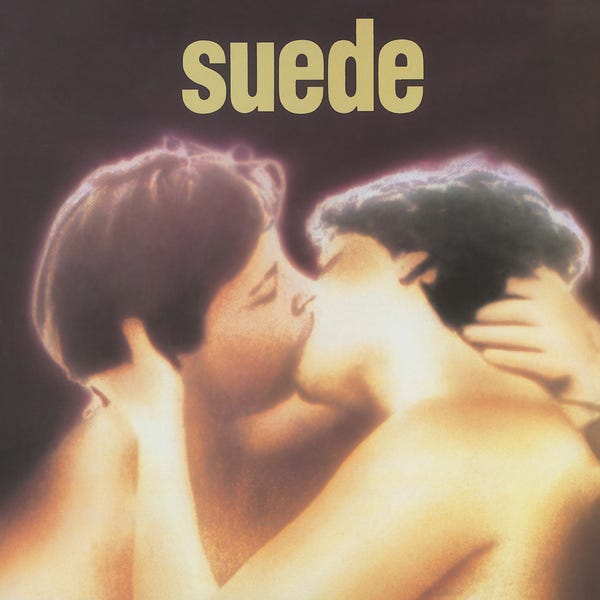

Suede’s early singles set a high bar for their debut self-titled album, one that most fans and critics felt they surpassed or met at the time, especially as it earned them the coveted Mercury Music Prize in 1993 (beating out PJ Harvey’s Rid of Me, New Order’s Republic, and, er, Sting’s Ten Summoner's Tales). Whether intentionally or not, Suede’s early singles and the feverish anticipation for the debut album mirrored the early rise of the Smiths, making it hard for the press (and fans alike) to ignore the similarities. In his memoir, Coal Black Mornings, Brett Anderson is open about his love and admiration for the Smiths and their influence on Suede’s sound, style, and visual presentation. Both Anderson and Morrissey understood the power and allure of album art. Morrissey cheekily employed a backside photo of model George O'Mara to underscore homoerotic themes on the sleeve for “Hand in Glove.” Anderson used the image of a naked woman covered in body paint to resemble a man’s suit, her face dabbled with faux stubble and holding a cigar in one hand and a gun in another, nods to the ambiguous sex and violence suggested in the lyrics to “The Drowners.” Both classic sleeve designs defined the aesthetic styles forever linked to their bands, epitomized by each eponymous debut's cover art: a still from Andy Warhol's 1968 film Flesh, featuring actor Joe D'Allesandro, for The Smiths; a photo from 1991’s Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs taken by Tee Corinne of an androgynous couple kissing on the cover of Suede.

In many respects, Suede and The Smiths feel like bookends of a story I entered mid-way through. The Smiths were my gateway to a musical world beyond the American Top 40. Having discovered them circa The Queen Is Dead, I simultaneously made my way backwards and forwards through their catalogue, exploring the myriad other bands collectively filed under “alternative.” While there are many artists I found and fell in love with during this period, something fundamentally changed with Suede. They flipped a switch. Suddenly, it felt like Suede turned on the lights in the dark room I had been living in, and I was seeing a side of myself that I had been trying to avoid. I could no longer deny my sexual confusion or avoid the struggle between who I felt I was inside and the person I was presenting to the world. Suede understood what it felt like to be hiding in plain sight, how the fear of violence, rejection, and disdain can lead someone to suppress their desires and true nature simultaneously as they search dark alleys and back pages of newspapers for both physical and emotional connections. Illicit, implied, and immeasurably thrilling, “The Drowners,” “Metal Mickey,” and “Animal Nitrate” spoke of a world in which I was yearning to be the main character but was far too skittish and ashamed to ever explore. Those singles soundtracked my first year of university, almost exclusively through headphones, as I worried that playing them out loud in my dorm room would draw unwanted attention and disdain from my overly macho and masculine dormmates.

Suede came out on March 29, 1993, just as the winter semester ended and I headed home for the summer. I listened to it incessantly, mainly in the solitude of my car, dubbed onto a cassette with The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars on the flip side. A few months later, on June 5, I got within touching distance when Suede made their Canadian debut at Toronto’s Palladium. I still have a sense of the electricity in the air that night, of a palpable feeling that some kind of chemical reaction was happening to me in real-time as they finished each song. It wasn’t longing or lust after the band members, but a desire to experience the youthful abandon I heard and felt in the music. They were the living embodiment of the self-acceptance and self-confidence I was still years away from granting myself; through the music, I could practice — if not fully embrace — becoming the person I yearned to be.

Listening to it today, Suede feels far fresher than a 32-year-old record has any right to be. It’s not a perfect album by any stretch (I have similar criticisms to those Anderson shares in Coal Black Mornings). Still, given the immense pressure and scrutiny, Suede delivered a solid, supreme debut. “Animal Nitrate” never fails to excite me; it’s far and away my favourite of the early singles and in contention for my favourite Suede song of all time. “Pantomime Horse” offers stiff competition in that race, thanks to Anderson's and Butler’s efforts to one-up each other. The former delivers both his most affecting lyrics and vocal performance of the album; the latter cements his status as a guitar god with a bridge that makes my knees quiver. They find that exact synergy on the piano ballad closer “The Next Life,” the song they opened with on the tour in 1993.

Conversely, the recorded version of “Moving,” blistering and highly-charged in their live set at the time, suffers from some regrettable production choices that leave it flat but nowhere as dull as the anodyne, by-the-numbers “Animal Lover.” Suede had far superior B-sides that would have better served the record as a whole, but my early critiques of “She’s Not Dead” (“Meh,”) and “Breakdown” (second-tier “Where the Pigs Don't Fly”) have softened in the intervening years (“Breakdown” features one of my favourite Anderson lyrics: “Does he only come? / Does your love only come? / Does he only come in a Volvo?”)

You could say that the best way to experience any band’s oeuvre is to listen chronologically, but when it comes to Suede, it’s the only way. Whether you go in for the poppy burlesque strip-tease chorus of “The Drowners” or the maudlin prog-rock grandiosity of “Pantomime Horse,” Suede was (and still is) the perfect introductory record for their catalogue. Time and hindsight highlight the signals and signs of the inter-band dynamics and the break-up and re-inventions to come, but in 2025 as in 1993, Suede’s debut bristles with the energy and vigour of a band setting down the first chapter of their story, one whose end no one could have predicted at the time, parallels to other band be damned.

![the act of just being [t]here](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!moQy!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fedc03f78-2893-4045-9600-2bacb96b8fa5_1080x1080.png)

![the act of just being [t]here](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!pLeR!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0d02a71c-d57a-4a4b-b90c-22191b1e1244_2688x512.png)