Before starting this retro-flection series, I was as unfamiliar with The Blue Hour as with Night Thoughts. Unfamiliar actually sounds like an understatement; I hadn’t ever listened to either, and they were the two Suede albums I felt most apprehensive about discussing. Historically, my interest eight albums into any band’s career is pretty low. It happened with Belle and Sebastian, R.E.M., the Manic Street Preachers, and Radiohead. The list is longer than I’d like to admit. Still, I don’t think I’m alone in finding myself less than actively engaged in late-career releases, especially after a prolonged hiatus.

So I’ve come to Suede’s 2018 album The Blue Hour with a certain trepidation and a sense of distance compounded by another obstacle: long-form content creation fatigue. Don’t get me wrong: this series has been one of the most rewarding projects I’ve undertaken. It’s rekindling my enthusiasm for Suede’s music and has me already thinking about who I could do a similar reflection on next. That said, writing about The Blue Hour has lately felt more like a duty than a pleasure, and given that Night Thoughts ended up being an unexpected emotional peak for this project so far, I have been leery that this chapter on The Blue Hour will be something of a letdown and altogether less than the others.

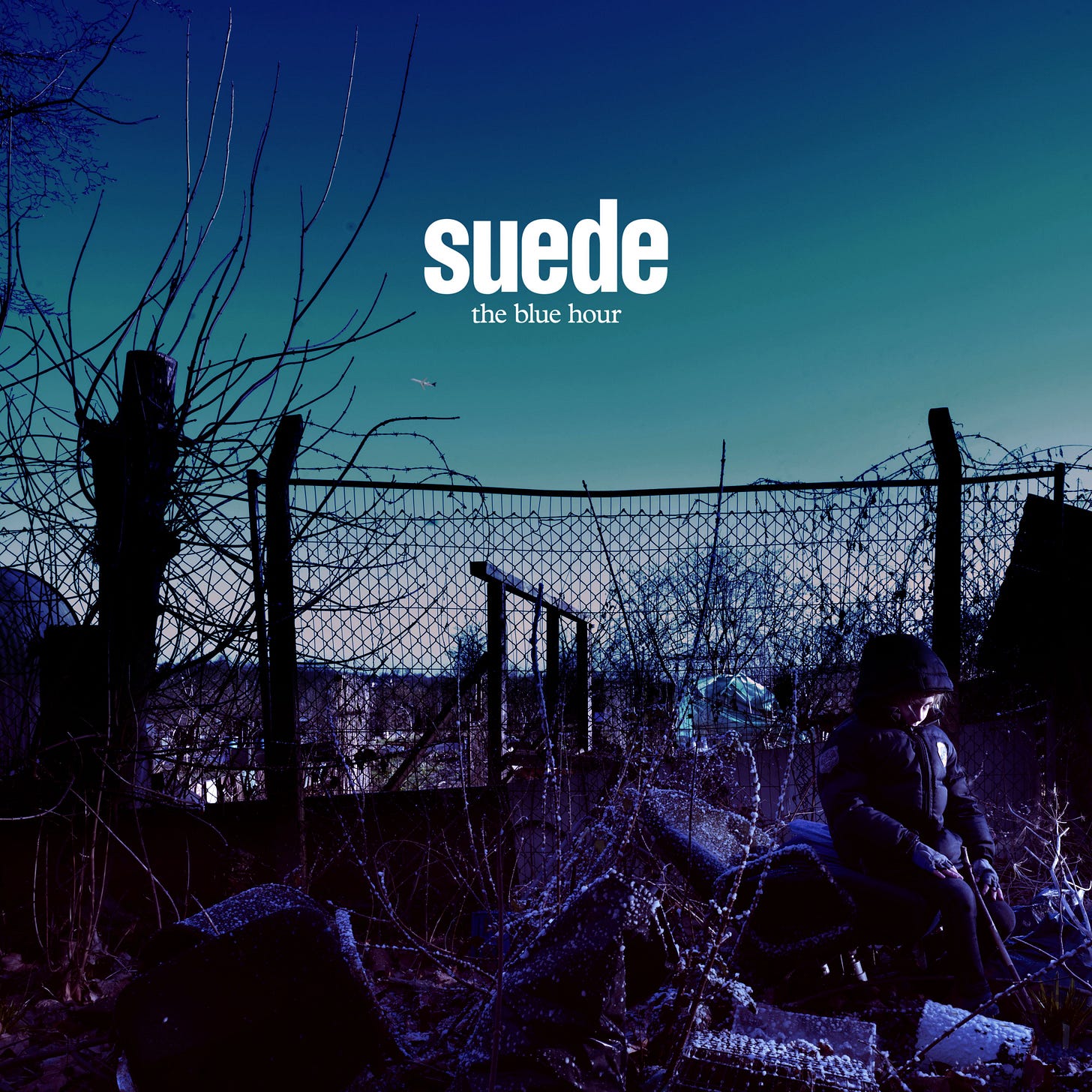

Released in September 2018, The Blue Hour was produced by Alan Moulder (famous for his work with the Jesus & Mary Chain, Ride, and Nine Inch Nails), a break from familiar and frequent collaborator Ed Buller, who returned for Bloodsports and Night Thoughts. Musically, The Blue Hour trades some of Night Thoughts’ urgency for more expansive textures: full orchestras and a strong, if non-linear, undercurrent of rural unease. It’s a shift in setting from the urban decadence and nightlife living of classic Suede, and the more suburban, domestic scenes typical of their previous post-reformation records, which makes sense if you think of Suede in 2018 as needing to find refuge and a change of pace and scenery to keep the creative fires burning.

The Suede that made The Blue Hour in 2018 is not the Suede I fell in love with a quarter of a century earlier, but I tried not to judge the album in comparison to their past work, and instead to meet Suede where they were at the time of its recording. I made a point of listening without leaning on easy comparisons with work I’m more familiar with, to clear the slate of my affection for Night Thoughts, and to hear what they’d created with as little bias as possible.

“As One” opens The Blue Hour with a sense of cinematic grandeur that’s almost ironic, given that Night Thoughts, the album with an actual accompanying film, never quite reached this scale. The arrangement comes in high-stakes and unapologetic, Brett Anderson’s lyrics showing a storyteller’s restraint: suggestive, atmospheric, and rich in mood without tipping into over-explanation. Like the first chapter of a novel, it creates a setting, introduces a tone, and creates intrigue. The band themselves have described it as the “keystone” for the record, with Anderson calling it the song that suggested the path forward for the whole album, even if it is something of an outlier amongst the tracklisting.

That sense of narrative possibility flows into “Wastelands,” which plays more recognizably to the Suede template. That’s not a slight; “Wastelands” reminds me of just how firmly Suede have established their own musical DNA. It also introduces spoken-word elements that pepper the album, reinforcing the idea that The Blue Hour, more than any of Suede’s previous attempts at a “concept album,” is meant to function as a whole, eschewing individual earworm moments for a more cohesive, collective mood. Nowhere is that sense of storyline more evident than on “Mistress.” String-laden and nearly drumless, it’s the story of a boy discovering his father’s affair, steeped in melodrama and sounding like it could have been lifted right from the score of a tragic musical. That is a slight, but only a minor one, given that “mistress” shows a restraint and focus that keeps it from going too far over the top.

But when “Beyond the Outskirts” takes a sudden detour into heavy metal guitar riffing, that sense of cohesiveness momentarily starts to fracture. I experienced similar jolts of the unexpected the first time I listened to Night Thoughts (the transition between “When You Are Young” and “Outsiders” is the first that springs to mind), but the contrast of heavy guitar layers on “Beyond the Outskirts” feels slightly at odds with the song’s lyrical tone. The metallic streak continues into “Chalk Circles.” The band has spoken about wanting something weirder and more stripped down, and it delivers a chant-like detour that segues directly into the next track, “Cold Hands.” Riff-heavy, taut, and energized by Alan Moulder’s production, “Cold Hands” finds the sweet spot where I could hear it living happily outside the album’s framework.

That energy flows into “Life Is Golden,” The Blue Hour’s first single, accompanied by a video filmed in a Chernobyl-affected town. Anderson has called it one of the few tracks he can hear in isolation, and I hear that, too. I would happily add “Life Is Golden” to a Suede best-of playlist without needing the rest of the record around it.

“Roadkill” strips things back to Anderson’s spoken-word performance over unsettling atmospherics. It’s intriguing in concept, but it initially leaves me feeling like I’m losing the plot to The Blue Hour. Repeated listens help give the song a place in the greater context of the album overall. It’s a brief interlude that dovetails into the wide-screen scope of “Tides.” By the time I reach “Don’t Be Afraid If Nobody Loves You,” I’m aware of a certain sameness setting in. It’s a good song, but I can’t recall its nuances once it’s over. That is mostly true of all these songs, reminding me that these are first impressions, unshaped by nostalgia. Whether they deepen will depend on how often I revisit The Blue Hour, if at all.

“Dead Bird” is little more than a 27-second fragment, a field recording of Anderson and his son burning a dead bird. It adds a small, macabre brushstroke to the album’s overall mood. The interlude makes it clear that Suede isn’t playing by any one set of rules, and “All the Wild Places” reinforces this break with expectation and pop tropes by pairing Anderson’s voice with just an orchestra. The sweeping strings continue with “The Invisibles”, a lush, string-driven piece that feels the most Suede-coded on the album in part due to Anderson’s vocal longing for connection against a backdrop of isolation.

“Flytipping” closes the album in cinematic style, echoing motifs from “As One” and picking up on the storytelling and melodrama threads from “Mistress,” with its tale of a couple discarding their possessions to move on to a new life. “‘Cause the worms in the ground / And the crows as they circle round,” sings Anderson against the haunted arrangement, “Don’t need these things to cling to / The road’s their playground.” As the couple makes their way “to the verges,” so too does Suede, moving as far away from the council home where “he broke all your bones” as they’ve ever been.

Since starting to delve into The Blue Hour, I’ve had this nagging sense that it reminds me of something and elicits a feeling for me that I could not put my finger on. I was walking around the house with my headphones on, the overwrought and hyper-orchestrated coda of “Flytipping” swirling in my head. I walked into the living room where my mother-in-law was streaming something from her Britbox account, and that’s when I made the connection: The Blue Hour reminds me of those British countryside detective dramas my mother-in-law loves watching—pastoral, polite, but highly discomfiting and sometimes heightened to the point of surrealism. They aren’t my favourite types of programs to watch, but while she’s yielding the remote, I’ll indulge, but I rarely get as engaged in the story the way she does.

And perhaps that’s the point I’m at in my relationship with The Blue Hour. I can appreciate its vision and scope as a cohesive piece of work, the evolution of Suede’s world-building sound, and its foray into more personal narratives. It’s an album I admire, but not one that I love or feel compelled to visit often.

If my default setting truly is “eighth-album apathy,” then The Blue Hour isn’t going to be the reset record to break me out of that cycle. And admittedly, it’s dimmed my rekindled infatuation with Suede somewhat. Still, more importantly, it’s reminded me that, even in their more difficult moments, there’s ambition, craft, and a willingness to take the long way around that many bands wouldn’t ever dare explore.

Not every chapter has to have a happy ending to make the whole story worth investing in.

![the act of just being [t]here](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!moQy!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fedc03f78-2893-4045-9600-2bacb96b8fa5_1080x1080.png)

![the act of just being [t]here](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!pLeR!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0d02a71c-d57a-4a4b-b90c-22191b1e1244_2688x512.png)

My interest with Radiohead also evaporated after their 8th album - I could not get into their 9th at all, but I think I was just at a different place in my life where I no longer identified with Yorke.